#193: Break out the Django testing toolbox

Sponsored by us! Support our work through:

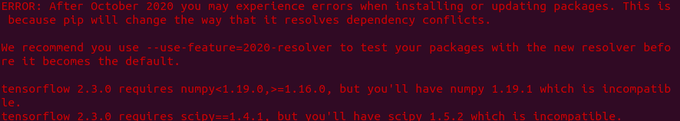

Brian #1: Start using pip install --use-feature=2020-resolver if you aren’t already

- Mathew Feickert

You may see something interesting when you run pip

This is not a problem. Do not adjust your sets.

- But, you should be aware of it.

Especially if you install from requirements generated with

pip freeze, you’ll want to use--use-feature=2020-resolvereverywhere:$ python -m pip install --use-feature=2020-resolver -r requirements_original.txt $ python -m pip freeze > requirements_lock.txt $ python -m pip install --use-feature=2020-resolver -r requirements_lock.txtOtherwise, you may run into issues

Michael #2: Profiling Python import statements

- Conversation with Brandon Braner lead to import-profiler

- A basic python import profiler to find bottlenecks in import times.

- Not often a problem, imports can be an issue for applications that need to start quickly, such as CLI tools.

- Goal of import profiler is to help find the bottlenecks when importing a given package.

- Example

from import_profiler import profile_import with profile_import() as context: # Anything expensive in here import requests # Print cumulative and inline times. The number of + in the 3rd column # indicates the depth of the stack. context.print_info()

Output:

umtime (ms) intime (ms) name

83 0.5 requests

55 0.5 +packages.urllib3.contrib

54.1 0.3 ++

53.1 0.7 +++connectionpool

6.3 1.1 ++++logging

...

Brian #3: Django Testing Toolbox

- Matt Layman

- Testing packages commonly used on Django projects

- Techniques Matt uses

- packages

- pytest-django - duh

- factory_boy - fake data

- django-test-plus - beefed up TestCase with tons of helper utilities

- techniques

- Using TestCase and test classes instead of functions

- Arrange, Act Assert structure

- In-memory SQLite database

- Disable migrations while testing

- faster password hasher

- Use your editor effectively to run tests

Michael #4: Pandas-profiling

- Recommended by Oz

- Considering the fact that Data Science users are almost the majority now for Python, I thought it would be nice to spread the word of pandas-profiling package.

- This package enables you to do Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) with a single command. It is really useful to understand what percent of the data is NULL, or how it is distributed.

I used to do these steps manually and it was quite time consuming. Now it is a breeze.

Generates profile reports from a pandas

DataFrame. The pandasdf.describe()function is great but a little basic for serious exploratory data analysis.pandas_profilingextends the pandas DataFrame withdf.profile_report()for quick data analysis.- Features

- Type inference: detect the types of columns in a dataframe.

- Essentials: type, unique values, missing values

- Quantile statistics like minimum value, Q1, median, Q3, maximum, range, interquartile range

- Descriptive statistics like mean, mode, standard deviation, sum, median absolute deviation, coefficient of variation, kurtosis, skewness

- Most frequent values

- Histogram

- Correlations highlighting of highly correlated variables, Spearman, Pearson and Kendall matrices

- Missing values matrix, count, heatmap and dendrogram of missing values

- Text analysis learn about categories (Uppercase, Space), scripts (Latin, Cyrillic) and blocks (ASCII) of text data.

- File and Image analysis extract file sizes, creation dates and dimensions and scan for truncated images or those containing EXIF information.

- Nice examples too

- Census Income (US Adult Census data relating income)

- NASA Meteorites (comprehensive set of meteorite landings)

- Titanic (the "Wonderwall" of datasets)

- NZA (open data from the Dutch Healthcare Authority)

- Stata Auto (1978 Automobile data)

- Vektis (Vektis Dutch Healthcare data)

- Colors (a simple colors dataset)

Brian #5: Interfaces, Mixins and Building Powerful Custom Data Structures in Python

- Redowan Delowar

- “Supercharging Python's built-in data structures”

- Discussion of interfaces, abstract base classes, mixins, and Python

- Class hierarchies and utilizing interfaces, ABCs (informal and formal), mixins, etc. are less common in Python than in some other languages, but you can still use them to do some really cool things.

- I especially liked the introduction to the concepts and why they are useful, as well as why ABCs are different than interfaces.

- “Interfaces can be thought of as a special case of Abstract Base Classes

"It’s imperative that all the methods of an interface are abstract methods and the classes don’t store any state (instance variables). However, in case of abstract base classes, the methods are generally abstract but there can also be methods that provide implementation (concrete methods) and also, these classes can have instance variables."

- Shows an example, and goes on to discuss mixins, a parent class that provides functionality to subclasses but is not intended to be instantiated itself.

Michael #6: Pickle’s 9 flaws

- Python’s pickle module is a very convenient way to serialize and de-serialize objects. It needs no schema, and can handle arbitrary Python objects. But it has problems. This post briefly explains the problems.

- Via pycoders.com

- Article by Ned Batchelder

- Insecure - The insecurity is not because pickles contain code, but because they create objects by calling constructors named in the pickle. Any callable can be used in place of your class name to construct objects.

- Old pickles look like old code - if your code changes between the time you made the pickle and the time you used it, your objects may not correspond to your code.

- Implicit - they will serialize whatever structure your object has.

- Over-serializes - They serialize everything in your objects, even data you didn’t want to serialize. For example, you might have an attribute that is a cache of computation that you don’t want serialized.

- __init__ isn’t called - Pickles store the entire structure of your objects. When the pickle module recreates your objects, it does not call your __init__ method, since the object has already been created.

- Python only - Pickles are specific to Python, and are only usable by other Python programs.

- Unreadable - A pickle is a binary data stream (actually instructions for an abstract execution engine.) If you open a pickle as a plain file, you cannot read its contents.

- Appears to pickle code - Functions and classes are first-class objects in Python: you can store them in lists, dicts, attributes, and so on. Pickle will gladly serialize objects that contain callables like functions and classes. But it doesn’t store the code in the pickle, just the name of the function or class.

- Slow - Compared to other serialization techniques, pickle can be slow as Ben Frederickson demonstrates in Don’t pickle your data.

Extras:

Michael:

- More on

Pathlibby Brett Ables:text = Path(file).read_text() - I was a guest on A Question of Code podcast. Ed, Tom, and I discussed:

Why is coding in Python such fun? And why is it so good for beginners and experts alike? Why might Python give you tangible results faster than JavaScript? And once you've learnt some Python, what are your career options? Find out all this and more in this week's pythonic installment of A Question of Code.

Joke

- (via Aaron Brown)

- By Caitlin Hudon 👩🏼💻 @beeonaposy:

- I have a Python joke, but I don't think this is the right environment.

Episode Transcript

Collapse transcript

00:00 Hello and welcome to Python Bytes, where we deliver Python news and headlines directly to your earbuds.

00:05 This is episode 193, recorded July 29th, 2020. I'm Michael Kennedy.

00:10 And I am Brian Okken.

00:12 And we've got a bunch of great stuff to tell you about. This episode is brought to you by us.

00:16 We will share that information with you later. But for now, I want to talk about something that

00:23 I actually saw today. And I think you're going to bring this up as well, Brian. I'm gonna let

00:27 you talk about it. But something I ran into updating my servers with a big warning in red when I pip

00:32 installed some stuff saying, your things are inconsistent. There's no way pip is going to

00:37 work soon. So be ready. And of course, that just results in frustration for me because, you know,

00:43 depend a bot tells me I need these versions, but some things don't require anyway, long story,

00:47 you tell us about it. Yeah, okay. So I was curious. I haven't actually seen this yet. So I'm glad that

00:52 you've seen it so that you have some experience. This was brought up to us by Matthew Fikart. And he

00:59 says he was running pip and he got this warning and it's all in red. So I'm gonna have to squint to read

01:04 this. Says, after October 2020, you may experience errors when installing or updating packages. This is

01:12 because pip will change the way it resolves dependency conflicts. We recommend that you use use features

01:18 equals 2020 resolver to test your packages. It shows up as an error. And I think it's just so that people

01:24 actually read it. But I don't know if it's a real error or not. It's still it works fine. But it's it's going to be an error

01:30 eventually. Okay, so this is not a problem to not adjust your sets actually do adjust your sets.

01:35 What you need to be aware of is the changes. So we've got a we I think we've covered it before,

01:40 but we've got a link in the show notes to the pip dependency resolver changes. And these are good

01:47 things. But one of the things that Matthew pointed out, which is great, and we're also going to link to

01:52 an article where he discusses where, like how his problem showed up with this. And it's around projects

01:59 that use some people use poetry and other things. And I can't remember the other one,

02:03 that does things like lock files and stuff. But a lot of people just do that kind of manually. And what

02:10 you often do is you have like a, your original set of requirements that are just your, like the handful

02:16 of things that you immediately depend on with no versions or or with minimal version rules around

02:23 it. And you say have installed this stuff. Well, that actually ends up installing a whole bunch of

02:29 all of your immediate dependencies, all of their dependencies and everything. So if you want to

02:34 lock that down, so that you're only installing the same things again and again, you say pip freeze,

02:39 and then pipe that to a, like a lock file. And then you can use that, I guess, a common pattern.

02:46 It's not the same as pip env's lock file and stuff, but it can be similar anyway. And then if you use

02:52 that and pip install from that, everything should be fine. You're going to install those dependencies.

02:56 The problem is if you don't use the use 2020 resolver feature to generate your lock file,

03:05 then if you do use it to install from your lock file, there may be incompatibilities with those.

03:12 So the resolvers actually try is actually, there's good things going on here, having pip do the

03:17 resolver better. But the quick note we want to say is don't panic when you see that red thing,

03:22 you should just try the use features 2020 resolver. But if you're using a lock file, use it for the

03:28 whole process, use the new resolver to generate your original lock file from your original stuff,

03:34 and then use it when you're installing the requirements lock file. There's also information

03:39 on the IPA website. They want to know if there's issues. This is still in a, it's available, but we're

03:46 still, there's still maybe kinks, but I think it's pretty solid. Not enforced, but warning days. Yeah. And I

03:52 kind of actually really like this way of rolling out a new feature and in a behavior change is to,

03:57 to have, to have, have it be available as a flag so that you can test in a, in a, not a pre-release,

04:04 but an actual release, and then, change the default behavior later. But so the reason why we're

04:10 bringing this up is October is not that far away. And October is the date when that's going to change

04:17 to not just the flag behavior, but the default behavior. So yes, go out and make sure these things

04:22 are happening. And if you completely ignore us when things break in October, the reason is probably

04:28 that you need to regenerate your lock file. Yep. So in principle, I'm all for this. This is a great idea.

04:34 It's going to make sure that things are consistent by looking at the dependencies of your libraries.

04:40 However, two things that are driving me bonkers right now are systems like depend a bot or pie up,

04:50 which are critically important for making sure that your web apps get updated with say like security

04:57 patches and stuff. Right. So you would do this like a, you know, pip freeze your dependencies,

05:02 and then it has the version. What if say you're using Django and there's a security release around

05:09 something in there, right? Unless you know to update that, it's always just going to install the one that

05:14 you started with. So you want to use a system like depend a bot or pie up where it's going to look at

05:19 your requirements. It's going to say, these are out of date. Let's update them. Here's the new one.

05:24 However, those systems don't look at the entirety of what it potentially could set them to. It says,

05:31 okay, you're using doc opt. There's 0.16 a doc opt. Oh, except for the thing that is before it

05:37 actually requires doc opt 14 or it's incompatible. And as in incompatible as pip will not install that

05:44 requirements.txt any longer. But those systems still say, great, let's upgrade it. And you're like in

05:52 this battle of those things or like upgrading it. And then like the older libraries are not

05:59 upgrading or you get two libraries. One requires doc opt 16 or above. One requires doc opt 14 or lower.

06:05 You just can no longer use those libraries together. Now it probably doesn't actually matter. Like the

06:10 feature you're using probably is compatible with both, but you won't be able to install it anymore. And

06:14 my hope is what this means is the people that have these weird old dependencies will either loosen the

06:22 requirements on their dependency structure. Like we're talking about, right? Like this thing uses this

06:27 older version or it's got to be a new version or update it or something, because it's going to be,

06:33 there's going to be packages that are just incompatible that are not actually incompatible because of this.

06:38 Yeah. Interesting. Yes. Painful. I don't know what to do about it, but it's like literally this

06:43 morning I ran into this and I had to go back and undo what depend a bot was trying to do for me

06:48 because certain things were no longer working, right? Or something like that. Interesting. Yeah. So

06:53 does depend a bot depend a bot? Depend a bot. Yeah. That's the thing that GitHub acquired that

06:58 basically looks at your various package listings and says, there's a new version of this. Let's pin it to

07:03 a higher version. And it comes as a PR. Okay. That was my question. It comes as a PR. So if you

07:08 had testing around in a CI like environment or something, it could catch it before it went

07:14 through. Yes. You'll still get the PR. It'll still be like be in your GitHub repo, but the CI

07:19 presumably would fail because the pip install step would fail. And then it would just know that it

07:25 couldn't auto merge it. But still it's like, you know, it's, you're like constantly like trying to

07:32 push the water, the tide back because you're like, stop doing this. It's driving me crazy. And they're,

07:38 there are certain ways to like link it, but then there's just a force it to certain boundaries.

07:42 But anyway, it's, it's like, it's going to make it a little bit more complicated. Some of these

07:46 things. Hopefully it considers this. Well, maybe depend upon it can update to do this.

07:50 Wouldn't that be great. Yep. That would be great. Well, speaking of packages, the way you use packages

07:57 is you import them once you've installed them, right? Yes. So Brandon Branner, Branner was talking on

08:03 Twitter with me saying like, I have some imports that are slow. Like how can I figure out what's

08:08 going on here? And this led me over to something may have covered a long time ago. I don't think so,

08:15 but possibly called import dash profiler. You know this? No, this is cool. Yeah. So one of the things

08:21 that can actually be legitimately slow about Python startup code is actually the imports. So for example,

08:30 like if you import requests, it might be importing like a ton of different things,

08:35 standard library modules, as well as external packages, which are then themselves importing

08:40 standard library modules, et cetera, et cetera. Right. So you might want to know what was slow and what's

08:45 not. And it's also not just, it's not like, just like a C include it's a imports actually run code.

08:52 Yes, exactly. It's not something happening at compile time. It's happening at runtime.

08:57 So every time you start your app, it goes through and it says, okay, what we're going to do is want

09:01 to execute the code that defines the functions and defines the methods and potentially other code as

09:06 well. Who knows what else is going on? So there's a non-trivial amount of time to be spent doing that

09:13 kind of stuff. For example, I believe it takes like half a second to import requests, just requests.

09:20 Interesting.

09:21 I mean, obviously that depends on the system, right? You do it on MicroPython versus on like a

09:25 supercomputer, the time's going to vary, but nonetheless, like there's a non-trivial amount

09:30 of time because of what's happening. So there's this cool thing called import profiler, which all you

09:34 got to do is say from import profiler, import, profile, import. Woo. Say that a bunch of times fast.

09:43 Written, it's fine. Spoken, it's funky. But then you just create a context manager around your import

09:49 statements. You say with profile import as context, all your imports, and then you can print out, you

09:55 say context.printinfo and you get a, like a profile status report.

09:59 That's cool.

10:00 Now I included a little tiny example of this for requests and what was coming out of it. If you look

10:05 at the documentation, it's actually much longer. So I'm looking here, I would say just, you know,

10:11 eyeballing it. There's probably 30 different modules being imported when you say import requests.

10:17 That's non-trivial, right? That's a lot of stuff. So this will give you that output. It'll say

10:23 here, this module imported this module, and then it has like a hierarchy or a tree type of thing. So

10:29 this module imported this module, which imported those other two. And so you can sort of see the

10:34 chain or a tree of like, if I'm importing this, here's the whole bunch of other stuff it takes with

10:39 it. Okay. Yeah. And it gives you the overall time. I think maybe the time dedicated to just

10:46 that operation and then the inclusive time or something. Actually, maybe it looks more like

10:51 83 milliseconds. Sorry, I had my units wrong instead of half a second, but nonetheless, it's like,

10:55 you know, you have a bunch of imports and your running code. Where is that slow?

10:59 You can run this and it basically takes three lines of code to figure out how much time

11:05 each part of that entire import stack. I want to say call stack of that execution, but it's

11:11 the series of imports that happen. Like you time that whole thing and look at it. So yeah,

11:16 that's, it's pretty cool.

11:16 That's neat. And also, I mean, there's, there's times where you want, you really want to get startup

11:22 time for something really as fast as possible. And this is part of it is, is your, the things you're

11:28 importing at your startup is non, sometimes non-trivial when you have something that you really want to

11:34 run fast.

11:35 Right. Like let's say you're spending half a second on startup time because of the imports.

11:39 You might be able to take the slowest part of those and import that in a function that gets called.

11:45 Right. So.

11:46 Yeah.

11:47 Import it later.

11:48 Yes.

11:48 You only pay for it at, if you're going to go down that branch, because maybe you're not going to

11:52 call that part of the operation or like that part of the CLI or whatever.

11:56 Yeah. And it's definitely one of those fine tuning things that you want to make sure you don't do this

12:00 too early, but, but for people packaging and supporting large projects, I think it's, it's a good idea to

12:07 pay attention to this and make sure to your import time. Like it'd be something that would be kind of

12:11 fun to throw in a test case for CI to make sure that your, your import time doesn't suddenly

12:16 go slower because something you depend on suddenly got slower or something like that.

12:21 Yeah. Yeah. Absolutely. And you don't necessarily know because the thing it depends upon that thing

12:26 changed, right? It's not even the thing you actually depend upon, right? It's very,

12:29 it could be very down, down the line. Yeah. And maybe you're like, we're going to use this other

12:33 library. We barely use it, but you know, we already have dependencies. Why not just throw this one in?

12:38 Oh wait, that's adding a quarter of a second. We could just vendor that one file that we don't really,

12:44 you know, and make it much, much faster. So there's a lot of interesting,

12:46 use cases here. A lot of time you don't care. Like for my web apps, I don't care for my CLI apps.

12:51 I might care. Yeah, definitely. Yeah. So I've been on this bit of a exploration lately, Brian,

12:57 and that's because I'm working on a new course. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. We're actually working on a

13:02 bunch of courses over at talk Python, some data science ones, which are really awesome. But the

13:06 one that I'm working on is Python memory management and profiling are, and, tips and tricks and data

13:13 structures to make all those things go better. Nice. So I'm kind of on this profiling bent.

13:18 And anyway, so if people are interested in that or any of the other courses that we're working on,

13:23 they can check them out over at training.talkpython.fm helps bring you this podcast and others and,

13:30 books. Thanks for that transition. But I, I'm excited about that because the profiling and stuff is one of

13:35 those things that often is considered kind of like a black art, something that you just learn on the job

13:40 and how do you learn it? I don't know. You just have to know somebody that knows how to do it or

13:44 something. So having some courses around, that's a really great idea. Thanks. Yeah. Also like,

13:48 when does the GC run? What is the cost of reference counting? Can you turn off the GC? What data

13:54 structures are more efficient or less efficient according to that? And all that kind of stuff.

13:58 It'll be a lot of fun. Cool. Yeah. So I've got a book. I actually want to highlight something. I've

14:03 got a link called, it's pytestbook.com. So if you just go to pytestbook.com, it actually goes to a

14:10 landing page that's on blog. That's kind of not really that active, but there is a landing page.

14:16 The reason why I'm pointing this out is because some people are transitioning. Some people are

14:21 finally starting to use three, eight more. There's people starting to test three, nine a lot, which is

14:26 great. There's pytest six just got released, not one of our items. And I've gotten a lot of questions

14:32 of, is the book still relevant? And yes, the pytest book is still relevant, but there's a couple of

14:38 gotchas. I will list all of these on that landing page. So they're not there yet, but they will be

14:44 by the time this airs. Time travel. Yeah. There's a Rata page on Pragmatic that I'll link to, but also,

14:49 but the main, there's a few things like there's, a database that I use in the examples as a tiny

14:55 DB and the API changed since I wrote the book. There's a little note to update your, update the setup

15:02 to pin the database version. And there's a, something, you know, markers used to be,

15:08 used to be able to get away with just throwing markers in anywhere. Now you get a warning if you

15:13 don't declare them. There's a few minor things that get changed, are changed to that make it

15:18 for new pytest users might be frustrating to walk through the book. So I'm going to lay those out

15:23 just directly on that page to have, have people get started really quickly. So pytestbook.com

15:29 is what that is. Awesome. Yeah. It's a great book. And you might be on a testing

15:33 bent as well. If I'm on my profiling one. Yeah, actually. So this is a Django testing

15:39 toolbox is an article by Matt Lehman. And I was actually going to think about having him on the

15:44 show and I still might on testing code to talk about some of the stuff, but he threw together,

15:48 I just wanted to cover it here. Cause it's a really great throw together of information.

15:52 That's a quick walkthrough of how Matt tests Django projects. And he goes through

15:58 some of the packages that he uses all the time and some interesting techniques,

16:03 the packages that there's a couple of them that I was familiar with. pytest Django,

16:08 which is like, of course, you're, of course you should use that. factory boy is the one

16:13 there's a lot of factory boys, one project. There's a lot of different projects to generate

16:18 fake data. Factory boys, the one Matt uses. So there's a highlight there. And then one that

16:23 I hadn't heard of before Django test plus, which is a beefed up test case. It maybe has other stuff

16:29 too, but it has a whole bunch of helper utilities to make it easier to check commonly tested things

16:34 in Django. So that's, that's pretty cool. And then some of the techniques, like one of the things that

16:40 people, some people trying to use pytest for Django get tripped up at is a lot of people think of pytest

16:47 is just functions only test functions only and not test classes. But there's a, there are some uses,

16:53 Matt says he really likes to use test classes. I mean, there's no, I mean, pytest allows you to use

16:59 test classes, but, you can use these derived test cases like, the Django test plus test case.

17:05 A couple of other things using a range act assert as a structure in memory SQLite databases when you

17:11 can get away with it to speed up because in memory databases are way faster than on file system

17:16 databases.

17:17 Yeah. And you don't have to worry about, dependencies or servers you got to run. It's

17:20 just colon memory. Boom. You connect to it and off it goes. Nice.

17:25 Yeah. one of the things I didn't get, I mean, I kind of get the next one disabling

17:29 migrations while testing. I don't know a lot about my database migrations or Django migrations,

17:35 or whatever those are, but apparently disabling them is a good idea. It makes sense. Faster

17:40 password hasher. I have no idea what this is talking about, but apparently you can speed

17:46 up your testing by having a pass faster password hasher. Yeah. A lot of times they'll, they'll

17:51 generate them. So they're explicitly slow, right? So like over at talk Python, I have, I use

17:59 pass lib, not Django, but pass lib is awesome. But if you just do say an MD5, it is like,

18:05 super fast, right? So if you say, I want to generate this and take this and generate it,

18:11 it'll come up with the hashed output, but because it's fast, people could look at that and say,

18:16 well, let me try like a hundred thousand words. I know and see if any of them match that, then

18:20 that's the password, right? You can use more complicated ones. And MD5 is a, not when you

18:25 want something like be encrypt or something, which is slower a little bit and better, harder

18:31 to guess. But what you should really do is you should like insert little bits of like salt,

18:36 like extra text around it. So even if it matches, it's not exactly the same, like you can't do those

18:41 guesses, but then you should fold it, which means take the output of the first time, feed it back

18:46 through, take the output of the second time, feed it back through a hundred, 200, 300,000 times. So

18:51 that if they try to guess, it's super computationally slow. I'm sure that's what it's talking about. So

18:56 you don't want to do that when you want your test to run fast because you don't care about hash

18:59 security during test. Oh yeah. That makes total sense. That's my guess. I don't know for sure,

19:04 but that's what I think what that probably means. The last tip, which is always a good tip is figure

19:09 out your editor so that you can run your tests from your editor because your cycle time of flipping

19:15 between code and test is going to be a lot faster if you can run them from your editor. Yep.

19:20 These are good tips. And if you're super intense, you have the auto run,

19:23 which I don't do. I don't have auto run on. I do it once in a while. Yeah. Yeah. Cool. Well,

19:29 back to my rant, let's talk about profiling. Okay. Actually, this is, this is not exactly the same

19:34 type of profiling. It's more of a look inside of data than of performance. So this was recommended to

19:41 us by one of our listeners named Oz. First name only is what we got. So thank you, Oz. And he is a data

19:48 scientist who goes around and spends a lot of time working on Python and doing exploratory data analysis.

19:54 And the idea is like going to grab some data, open it up and explore it. Right. And just start

20:00 looking around, but it might be incomplete. It might be malformed. You don't necessarily know exactly what

20:04 its structure is. And he used to do this by hand, but he found this project called pandas dash profiling,

20:10 which automates all of this. So that sounds handy. I mentioned before missing, no missing N O as in

20:18 the missing number, missing data explorer, which is super cool. And I still think that's awesome,

20:23 but this is kind of in the same vein. And the idea is given a pandas data frame, you know, pandas has a

20:30 describe function that says a little bit of detail about it. But with this thing, it kind of takes that

20:35 and supercharges it. And you can say DF dot profile report, and it gives you all sorts of stuff. It does

20:42 type inference to say things in this column are integers or numbers, strings, date times, whatever.

20:48 It talks about the unique values, the missing values, quartile statistics, stuff, descriptives,

20:54 that's like mean mode, some standard deviation, a bunch of stuff, histograms, correlations,

21:01 missing values. There's the missing note thing. I spoke about text analysis of like categories and

21:07 whatnot, file and image analysis, like file sizes and creation dates and sizes of images and like

21:13 all sorts of stuff. So the best way to see this is to look at an example. So in our notes, Brian,

21:18 do you see where there's like a has nice examples and there's like the NASA meteorites one. So there's

21:22 an example for like the US census data, a NASA meteorite one, some Dutch healthcare data and so on.

21:29 If you open that up, you get it. You see what you get out of it. Like it's pages of reports of what was in

21:34 that data frame. Oh, this is great. Isn't that cool? It's got like, it's, it's tabbed and stuff. So it's tabbed.

21:40 It's got warnings. It's got pictures. It's got all kinds of analysis. It's got histogram graphs and you can

21:47 like hide and show details and the details include tabbed on, you know, I mean, this is a massive dive into what the

21:55 heck is going on with this data correlations heat maps. I mean, this is the business right here. So

22:02 this, this is like one line of code to get this output. This is great. This is like replaces a couple

22:09 interns at least. Sorry interns, but yeah, this is a really cool. So I totally recommend if this sounds

22:18 interesting, you do this kind of work, just pull up the NASA meteorite data and realize that like that

22:24 all came from, you know, importing the thing and saying DF profile report basically. And you get this,

22:30 you can also click and run that in binder and Google collabs. You can go and interact with it live if you

22:36 want. Yeah. I love the, I love the warnings on these, some of the things that can like saying some

22:41 of the variables that show up of like, there's some of them are skewed, like too many values at

22:46 one value that there's some of them have missing zeros showing. It does quite a bit of analysis for

22:52 you about the data right away. That's pretty great. Yeah. Yeah. The types is great because you can just,

22:57 I mean, you can have like hundreds or thousands of data points. It's not trivial to just, to just say,

23:04 oh yeah, all of them are true or false. All of them are, I know they're Booleans. You'd have to look at

23:09 everything first. So yeah. Yeah. It's one of those things that's like easy to adopt,

23:14 but looks really useful and it's also beautiful. So yeah, check it out. It looks great. I want to

23:18 talk about object oriented programming a little bit. Oh, okay. Actually, it's not something, I mean,

23:23 all of Python really is object oriented because we use, everything is an object really. Deep,

23:28 deep down, everything's a Py object pointer. Yeah. There's an article by Redewon Delaware called

23:35 Interfaces, Mix-Ins, and Building Powerful Custom Data Structures in Python.

23:39 And I really liked it because it's a Python focused, I mean, there's not a lot, I've actually been

23:45 disappointed with a lot of the object oriented discussions around Python. And a lot of them

23:50 are talk about basically, I think they're lamenting that the system isn't the same as other languages,

23:56 but it's just not. Get over it. This is a Python centric discussion talking about interfaces and

24:03 abstract base classes, both informal and formally abstract base classes using Mix-Ins. And it starts

24:11 out with the concept that people, there's like a base amount of knowledge that people have to have to

24:17 discuss this sort of thing and of understanding why they're useful and what are some of the downfalls

24:23 and upfalls or benefits and whatever. And so he actually starts by, it's not too deep of a

24:30 discussion, but it's an interesting discussion. And I think it's a good background to discuss it.

24:36 And then he talks about like one of the things you kind of get into a little bit and you go, well,

24:40 what's really different about an abstract base class and an interface, for instance?

24:45 And he writes interfaces can be thought of as a special case of an abstract base class. It's

24:51 imperative that all methods of an interface are abstract methods and that classes don't store

24:56 any data or any state or instance variables. However, in case of abstract base classes,

25:02 the methods are generally abstract, but there can also be methods that provide implementation,

25:06 concrete methods, and also these classes can have instance variables. So that's a nice distinction.

25:12 Yeah.

25:13 Then mix-ins are where you have a parent class that provides some functionality of a subclass,

25:18 but it's not intended to be instantiated itself. That's why it's sort of similar to abstract base

25:24 classes and other things. So having all this discussion from one person in a good discussion,

25:29 I think is a really great thing. And there are definitely times I don't pull into class hierarchies

25:36 and base classes that much, but there's times when you need them and they're very handy. So it's cool.

25:42 Yeah, this is super cool. Actually, I really like this analysis. I love that it's really Python focused

25:47 because a lot of times the mechanics of the language just don't support some of the object oriented

25:54 programming ideas in the same way, right? Like the interface keyword doesn't exist, right? So this

26:01 distinction, you have to, you have to make it in a conventional sense. Like we come up with a

26:06 convention that we don't have concrete methods or state with interfaces, right? But there's nothing,

26:12 there's not like an interface keyword in Python. So I like it. I'm a big fan of object oriented

26:17 programming. And I'm very aware that in Python, a lot of times what people use for classes is simply

26:25 unneeded. And I know where that comes from. And I want, I want to make sure that people don't

26:29 overuse it, right? If you come from Java or C#, or one of these OOP only languages,

26:34 everything's a class. And so you're just going to start creating classes. But if what you really want

26:38 is to group functions and a couple of pieces of data that's like shared, that's a module, right?

26:43 You don't need a class, right? You could still say module name dot and get the list of them.

26:47 And it's, it's like a static class or something like that. But sometimes you want to model stuff

26:53 with object oriented programming. And understanding the right way to do it in Python is really cool.

26:57 This looks like a good one.

26:58 Yeah. And also, there is a built in library called ABC, or abstract base class within Python. And it

27:06 seems like a, for a lot of people, it seems like a mystery thing that only advanced people use,

27:11 but it's really not that complicated. And this article uses that as well and talks about it. So

27:16 it's good.

27:17 You know, one of my favorite things about abstract base classes and abstract methods is in PyCharm,

27:23 if I have a class that derives from an abstract class, all I have to write is class, the thing

27:28 I'm trying to create, parentheses, abstract class name, close parentheses, colon, and then

27:34 you just hit alt, alt enter, and it'll pull up all the abstract methods. You can highlight

27:38 them, say implement, it goes, boom, and it'll just write the whole class for you.

27:40 Wow.

27:41 But if it's not abstract, obviously it won't do that, right? So the abstractness will tell

27:45 the editor to like write the stubs of all the functions for you.

27:47 Oh, that'd be, that's a cool use, reason to use them.

27:50 That's almost reason to have them in the first place.

27:52 Yeah.

27:52 Almost.

27:53 Nice.

27:54 We've pickled before, haven't we?

27:55 Yeah.

27:56 Yeah, we have talked about pickle a few times.

27:58 Yes. Have we talked about this article?

27:59 I don't remember.

28:00 I don't think so. We have. Apologies. But it's short and interesting. So Ned Batchelder wrote

28:07 this article called Pickle's Nine Flaws. And so I want to talk about that. This comes to us

28:12 via piecoders.com, which is very cool. And we've talked about the drawbacks. We talked about

28:18 the benefits. But what I liked about this article is concise, but it shows you all the tradeoffs

28:22 you're making. Right? So quickly, I'll just go through the nine. One, it's insecure. And

28:29 the reason that it's insecure is not because pickles contain code, but because they create

28:33 these objects by calling the constructors named in the pickle. So any callable can be used

28:39 in place of your class name to construct objects. So basically it runs potentially arbitrary code

28:46 depending on where it got it from. Old pickles look like old code, number two. So if your code

28:51 changes between the time you pickled it and whatever, it's like you get the old one recreated back to

28:57 life. Like so if you added fields or other capabilities, like those are not going to be

29:01 there. Or you took away fields. They're still going to be there. Yeah, it's implicit. So they

29:06 will serialize whatever your object structure is. And they often over serialize. So they'll

29:11 serialize everything. So like if you have cache data or pre-computed data that you wouldn't ever

29:16 normally save, well, that's getting saved. Yeah. One of the weird ones that this has caught me out

29:22 before and it's just, I don't know, it's weird. So there you go. Is the dunder in it, the constructor

29:27 is not called. So your objects are recreated, but the dunder in it is not called. They're just the values

29:33 have the value. So that might set it up in some kind of weird state.

29:38 Like maybe pass it, fail some validation or something. It's Python only. Like you can't share

29:43 with other programs because it's like a Python only structure. They're not readable. They're binary.

29:48 It will seem like it will pickle code. So if you have like a function you're hanging on to,

29:55 you pass it along like some kind of lambda function or whatever, or a class that's been passed over

30:00 and you have a list of them or you're holding onto them and that you think that it's going to save that,

30:05 all it really saves is basically like the name of the function. So those are gone. And I think one of

30:12 the big, real big challenges is actually slower than things like JSON and whatnot. So, you know,

30:17 if you're willing to give up those trade-offs because it was super fast, that's one thing,

30:21 but it's not. And are you telling me that we covered it before?

30:24 We did cover it in 189, but I had forgotten. So it was like a couple months ago, right?

30:28 Yeah, it's a while ago. Anyway, it's good to go over it again.

30:32 Definitely.

30:32 Be careful with your pickling. All right. How about anything extra? That was our top six

30:37 items. What else we got?

30:38 I don't have anything extra. Do you have anything extra?

30:40 Pathlib. Speaking of stuff we covered before, we talked about Pathlib a couple of times. You

30:45 talked about Chris May's article or whatever it was around Pathlib, which is cool. And I said,

30:50 basically, I'm still, I just got to get my mind around like not using OS.path and just get into this.

30:56 Right. And people sent me feedback like, Michael, you should get your mind into this. Of course,

31:00 you should do this. Right. And I'm like, yeah, yeah, I know. However, Brett Abel sent over a

31:05 one-line tweet that may just like seal the deal for me. Like, this is sweet. So he said, how about

31:11 this? Text equals path of file dot read text. Done. No context managers, no open, none of that. And I'm

31:18 like, oh, that's okay. That's pretty awesome. Anyway, I just wanted to give a little shout out to

31:26 that like one liner because that's pretty nice. And then also I was just a guest on a podcast out

31:31 of the UK called a question of code or the host Ed and Tom and I discussed why Python is fun. Why is

31:38 it good for beginners and for experts? Why am I give you results faster than like tangible code or

31:45 tangible programs faster than say like JavaScript, career stuff, all kinds of stuff. So anyway, I linked

31:50 to that if people want to check that out. That's cool. Yeah. It was a lot of fun. Those guys are

31:54 running a good show over there. Yeah. I think I'm, I think I'm talking with them tomorrow.

31:57 Right on. How cool. One of the things I like about it is the accents just, you know,

32:02 cause accents are fun. So I was going to ask you, would you consider learning how to do a British

32:07 accent? Cause that would be great for the show. I would love to, I fear I would just end up insulting

32:13 all the British people and, not coming across really well, but I love British accents.

32:19 If we had enough Patreon supporters, I would be more than happy to volunteer to move to England to develop

32:26 a, maybe just live in London for a few years. Like if they're going to fund that for you, that would be

32:32 awesome. Yeah. London's a great town. Okay. All right. How about another joke? I'd love another joke. So this

32:39 one is by Caitlin Hudon, but was pointed out to us by Aaron Brown. So she tweeted this on Twitter and he's like, Hey,

32:48 you guys should think about this. So you ready? Yeah. Caitlin says, I have a Python joke, but I think,

32:53 I don't think this is the right environment. Yeah. So there's a ton of these like type of jokes. Like

32:59 I have a joke, but so this is a new thing, right? I don't know. It's probably going to be over by the

33:04 time this airs, but I'm really amused by these types of jokes. Yeah. I love it. This kind of touches

33:10 on the whole virtual environment, package of management, isolation, chaos. I mean, there was that XKCD

33:15 as well about that. Yeah. Okay. So while we're, while we're here, I'm going to read some from

33:19 Luciano. Luciano Romalo, he's a Python author and he's an awesome guy. Here's a couple other related

33:26 ones. I have a Haskell joke, but it's not popular. I have a Scala joke, but nobody understands it.

33:32 I have a Ruby joke, but it's funnier in Elixir. And I have a Rust joke, but I can't compile it.

33:38 Yeah. Those are all good. Nice. Cool. Nice. Nice. All right. Well, Brian, thanks for being here as

33:42 always. Thank you. Talk to you later. Bye. Thank you for listening to Python Bytes. Follow the show on

33:48 Twitter via at Python Bytes. That's Python Bytes as in B-Y-T-E-S. And get the full show notes at

33:54 Python Bytes.fm. If you have a news item you want featured, just visit Python Bytes.fm and send it our

33:59 way. We're always on the lookout for sharing something cool. On behalf of myself and Brian Okken,

34:04 this is Michael Kennedy. Thank you for listening and sharing this podcast with your friends and

34:08 colleagues.